Auto-mobile = autonomy + freedom

The nineteenth century was the century of the steam locomotive and the bicycle, of the frock coat and of formalism; the twentieth century was the century of progress and futurism with a new car that, once goggles and dust-coat were worn, inspired autonomy, independence and freedom. From the slow coaches and stagecoaches, in fact people switched to the steam-locomotive, but it was equally rigid and even bound by the railroads, the bicycle instead was slow, uncomfortable and its use limited by fatigue. The future will be of that of the car. At least for the next 200 years.

And Ada Negri, poet and writer at the turn of the two centuries and first and only woman to be admitted to the Academy of Italy, at the end of the first decade of the twentieth century writes on the Secolo XX : “… among modern pleasures there is no one that is better than or equal to that of a trip by car. In our vehicle, obedient only to us, leading us only where our wish wants, the need for freedom that is in us becomes a certainty of freedom, a sense of plenitude, of escape, of possession of space and time, which goes beyond the human limit”.

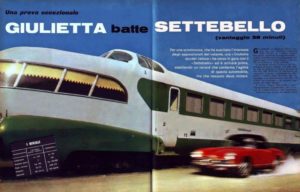

This new auto-mobile, increasingly more reliable and powerful, makes every other old vehicle appear outdated and perhaps even a bit “communist”, in the sense that in the past one could travel with other persons, friends or illustrious strangers, now instead one is alone or with whoever one wants. The airplane is another vehicle entering the scene at the same time as the car, and is also able to offer escape, freedom but above all speed and exclusivity. The car will win the challenge against the train but it will lose it against the airplane while progress – which runs faster than all of them – spreads their use, bringing these means back to the “communist” use of the past.

And from the desire for ever greater “speed”, great challenges were born since the end of the nineteenth century by land (various races), by sea (Nastro Azzurro) and by sky (Schneider Cup). The great races, those on the roads and the shared passion that fuels them, turned the history of the car into a real epic that will remain alive and socially shared until the seventies. The first car race, the Paris-Rouen, took place in France in 1894. Twelve years later, in 1906, in Italy, the first Targa Florio race was held and in 1927 the Mille Miglia; large-scale competitions destined to become two extraordinary sporting events that will attract the attention and emotion of the world even up to our times. Not only the official car manufacturers and the most famous drivers took part in them, but even car enthusiasts bewitched by the thrill of speed or by the ephemeral fame of the worldly and social aspects that such events represent and that originates from having participated in them.

Progress and speed, however, require sacrifices and victims “who must not stop the march of the survivors” as the “Sport Fascista” wrote in 1933, an inauspicious year that saw the death of Borzacchini, Campari, D’Ippolito and Toselli followed in previous years by those of Arcangeli, Ascari, Sivocci, Masetti, Brilli Peri, Bordino, Benini and many other glorious heroes of a fast and fearless Italy. Among the great drivers only Nuvolari, spared by the “grim reaper” on the racetrack, will die in his bed in 1953.

Enzo Ferrari in his 1962 book “My terrible joys” talked about how he loved to “feel the car and not only to drive it to be transported somewhere, but to meet the need and the pleasure of experiencing each reaction and feeling joined to it, as one single being”.

And in fact, the car is not only a weapon of war for the races of the brave drivers who compete driven by passion or by their patriotism; it is also a means of work, autonomy, freedom and often a romantic alcove of self-propelled love with which to reach shaded and secluded places. It is a travel and adventure companion as well as a means of work and transportation, which acquired over time more and more reliability together with more and more advanced and refined technologies until it reached our days, probably and slowly ending its life cycle, which has turned it into an anonymous and widespread means of transportation, no longer exclusive but very polluting.

Stefano d’Amico

On the cover: Umberto Boccioni, Red car (1904)

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes and belong to their respective owners..