Alfa Romeo and the Mille Miglia… a history in common

It is interesting how the history and the myth of Alfa Romeo were formed and developed in a process of osmosis with the history of the Mille Miglia itself, a legendary race of 1600 kilometers, Brescia-Rome-Brescia, on the roads of a pre-industrial Italy that was still very backward in road infrastructure. Reaching the finish line was already a success. And, as with the Targa Florio, the winning car would also have been successful on the market due to the “grip” that these two legendary car competitions had on the people. The Mille Miglia however, crossing a large part of central Italy in times when there were not videos or social networks, certainly constituted a larger show, better distributed throughout the territory and obviously free, fascinating and engaging, which aroused curiosity, gave strong media coverage and therefore it guaranteed a prestigious image to the manufacturer.

It is interesting how the history and the myth of Alfa Romeo were formed and developed in a process of osmosis with the history of the Mille Miglia itself, a legendary race of 1600 kilometers, Brescia-Rome-Brescia, on the roads of a pre-industrial Italy that was still very backward in road infrastructure. Reaching the finish line was already a success. And, as with the Targa Florio, the winning car would also have been successful on the market due to the “grip” that these two legendary car competitions had on the people. The Mille Miglia however, crossing a large part of central Italy in times when there were not videos or social networks, certainly constituted a larger show, better distributed throughout the territory and obviously free, fascinating and engaging, which aroused curiosity, gave strong media coverage and therefore it guaranteed a prestigious image to the manufacturer.

People from various regions could watch its passage crowded along 1600 kilometers of streets and cities, cheering almost directly for their champions and the different manufacturer, even from the windows and in the bars; a very heated cheer, goaded since the previous months in all the newspapers and on the radio. A test that tempered men and machines. Participating in it, side by side of various champions of the moment, was a great boast to which gentleman or aristocratic characters aspired; completing it, was a very important sporting result and, during the fascism period, maybe also political. In short, an international showcase that exalted not only our fearless drivers, but also the Italian technical and organizational skills.

People from various regions could watch its passage crowded along 1600 kilometers of streets and cities, cheering almost directly for their champions and the different manufacturer, even from the windows and in the bars; a very heated cheer, goaded since the previous months in all the newspapers and on the radio. A test that tempered men and machines. Participating in it, side by side of various champions of the moment, was a great boast to which gentleman or aristocratic characters aspired; completing it, was a very important sporting result and, during the fascism period, maybe also political. In short, an international showcase that exalted not only our fearless drivers, but also the Italian technical and organizational skills.

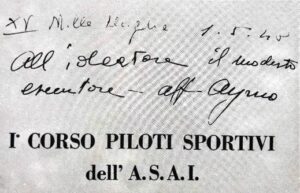

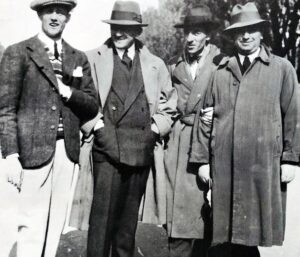

A dedication by Aymo Maggi, “modest performer”, to the “creator” Canestrini. The founders of the Mille Miglia, better known as “the four musketeers”, from left Aymo Maggi, Franco Mazzotti, Giovanni Canestrini, Renzo Castagneto.

I believe the human aspect that prevailed, rather than the technical one. It was the Man who won, a fearless and bold figure, even if the champion was often combined in the popular animus with the Manufacturer of which he was representative, but the human figure continued and continues to live in history and legend, with its “humanity”, its anecdotes and its… more or less tragic death. The car manufacturers, although they had excellent technicians and designers who generally remained in the shadows and are unknown to most, turned to the great champion to try to win or otherwise excel and derive the resulting media and commercial advantages. Therefore, every car manufacturers taking part in the race, and in particular Alfa Romeo but also those that sold tires or perhaps talcum powder, had well understood what an important marketing event was the Mille Miglia, immediately learning to take advantage of every promotional opportunity. In that period, particularly during the 1920s / 40s, Alfa was cutting edge, exploiting all its sporting successes to enhance its image and market everywhere, having immediately understood what a formidable advertising propellant was the racing car.

Much of his success in competitions and particularly in the Mille Miglia, where he can boast 11 overall victories, were due to the sagacity and shrewdness of Enzo Ferrari who since the early 1920s identified and hired the best technicians and the best drivers for Alfa Romeo. In the post-war period, however, Alfa, which literally came out of the terrible world conflict in pieces, certainly did not think about racing in a country that was also upset and impoverished and tried to recover by building fixtures, carpentry, gas kitchens and selling some obsolete six-cylinder cars.

It was during the 1950s when, with the birth of the new 1900 and Giulietta models, Alfa managed to revive and expand its markets. The conquest of the F1 World Championships in 1950 with Farina and 1951 with Fangio was also due to cars designed before the war and saved by it when the rest of the world, particularly Germany, was still in pitiful conditions. Therefore, removed Enzo Ferrari in 1939 by its sports management with a nice liquidation and set aside its competitive ambitions, Alfa from 1945 onwards it aimed only sporadically and with little determination to participate in the Mille Miglia because absorbed exclusively by the series production. The racing cars, built almost only to “satisfy” their designers, were never adequately prepared and followed as a race so demanding entailed. Moreover, since then some victories or a good placement in the lower classes was due only to a few private drivers with practically production cars.

The predictions of the first Mille Miglia, raced in 1927 and created by the fervent mind of four very important personalities in the automotive world of the time, Renzo Castagneto, Franco Mazzotti, Giovanni Canestrini,Aymo Maggi, gave the Alfa – already winner of the World Championship in the 1925 with the P2 single-seater – as a favorite in the Brescia race. However the most agile and light O.M. Superb 665 effortlessly beat the heavy and now obsolete Alfa RLSS designed by Merosi. At Portello, however, stolen from Fiat and brought, as we have said, by Enzo Ferrari, a great and innovative designer had arrived, Cav. Vittorio Jano, who had not been certain to look at the overtake of Merosi and already with the P2 had shown what he was capable. Since then and with him the music changed completely. Its potential was seen as early as 1927 with the debut of the small six-cylinder 6C 1500 Super Sport driven by Campari.

1927, Passo della Raticosa. Service station set up by Enzo Ferrari for the Alfa Romeo team. Here the no. 43 by Marinoni-Ramponi (driving) and Brilli Peri-Pesenti, encouraged by Ferrari himself, on the far left with his arm raised.

The 6C 1500 was the progenitor of a series of modern conception, light and easy to handle, with bright engines and high specific performance, far from the imposing and heavy cars that were still produced by many manufacturers and were the forerunners of future and wonderful Gran Turismo. They immediately proved unbeatable; they called “brooms” because in every competition they always took away the prizes up for grabs, even in inexperienced hands. Their glory, their absolute sublimation took place above all in the most demanding races, the endurances, such as the Mille Miglia or the Targa Florio that also had great political and international resonance. With the overall victory of Campari and Ramponi in the ’28 Mille Miglia, at the astonishing average of 84 kilometers per hour, Alfa consecrated its own brand and began to build its own legend. The Alfas immediately demonstrated not only their speed, but also all their great reliability, becoming the dream, hardly satisfied, of every motorist. Henry Ford apparently said “Every time I see an Alfa Romeo pass by, I lift my hat”!!!

The 6C 1750 Gran Sport, with its 100 hp, became the car to beat and from then on there was nothing more to be done for the O.M., the Lancias, the Bugattis or the fragile Maserati. The duels now took place in the House; like those legendary between Nuvolari and Varzi.

The other car manufacturers quite dismayed by the superiority of the Alfa and tried to run for cover even by hiring very strong drivers. Jano, however, feared only the very powerful Mercedes, aware that for his small 1750 it would have been difficult to win against those very powerful but also very heavy cars driven by the very strong Caracciola who, even if defeated in 1930, would certainly not have given up the field. And in fact the SSKL, strong with its 240 hp with a 7000 cc engine, in the hands of Rudolph Caracciola made the 1931 Mille Miglia its own without any problems. Second overall Campari and Marinoni with the Alfa 6C 1750 Gran Sport arrived anyway with only 11 minutes behind!

Left: Brescia, 1931. Caracciola’s Mercedes, assisted on the left by an elegant Renzo Castagneto. Right: Modena, San Venanzio straight, 1932. Scuderia Ferrari in full force away to Brescia for checks. Ferrari in dark suit and cap, behind him the 1750 for Baroness Avanzo. Resounding victory with 7 cars in the first 7 overall.

Therefore, in Alfa the development of an 8-cylinder in-line engine, obviously designed by Jano, of modern conception, in light alloy, twin-shaft with compressor, 2300 cc with 170 hp was accelerated. Another extraordinary car was born which, managed by Scuderia Ferrari, proved to be almost unbeatable in all kinds of competitions for over 10 years with the various updates, evolutions and improvements constantly made. It also won everywhere in all its versions, in road races, on the track, at the 24 Hours of Les Mans, etc. From 1932 the Alfa cars became unapproachable often in races where they were given for losers, thus enhancing the legend of Alfa Romeo and its drivers!

The Alfa won the Mille Miglia of ’33 without any problems with Nuvolari and Compagnoni followed by over 10 Alfa’s in the overall first places. In ’34, under incessant rain, Varzi won after an epic duel with Nuvolari, both obviously on Alfa. Pintacuda and Della Stufa won the Mille Miglia in ’35 with the P3, a powerful single-seater Grand Prix car transformed into a two-seater and adapted for the race, despite the limits of the regulations, thanks to Ferrari’s overbearing genius. Numerous Alfa always occupied the very first positions. The 8Cs were first brought to 2600 displacement by Scuderia Ferrari and subsequently to 2900 with double compressor and various modifications, gradually transforming these already powerful cars into vehicles far from the production ones. And for Alfa Romeo it was always a triumphal. We reached the Mille Miglia of 1938 where the magnificent spider 8C 2900 bodyworked by Touring and driven by Biondetti with the faithful mechanic Mambelli won at an average of over 135 km / h, an absolutely incredible performance that was improved only 15 years later, in 1953, from Ferrari of Giannino Marzotto.

Mille Miglia, 1935. Carlo Pintacuda and the Marquis Della Stufa on P3 at Passo della Raticosa. On the right, the Alfa 8C 2900 with Touring bodywork.

The popularity of Mille Miglia is due not only to the countless successes of an Italian company that exalted the souls and pride of the Regime and of common people, but above all to the intuition of those four brilliant organizers who together with the Reale Automobile Club of Brescia opened the registrations to the race also to most popular cars, those that circulated every day on few roads in Italy and animated the market and trade, that is to say the closed cars, the widespread and cheap Fiat, the refined Lancias, the most noble BMWs, etc., in short, cars strictly derived from the series and without any type of supercharging or other mechanical devices, thus establishing the National Sport Category. But even here Alfa Romeo was a bit of a master with the small and very agile 1750s in the 2000 category; the 8C 2300 and then the 6C 2500, although burdened by the weight of… iron and years, in the category over 2000, leaving the crumbs to the lower displacements. The definitive blow came at the anomalous 1940 edition (held on the Brescia-Cremona-Mantua circuit, Brescia Grand Prix) where the beautiful and more powerful 6C 2500 Spider Corsa Touring ofFarina and Mambelli was beaten by the extremely agile and light BMW 6c – 2000cc of Von Hanstein, also bodied by Touring. It should be remembered that in this edition the AutoAvio 815 (8 cylinders x 1500 cc) made its appearance, the first car built by Enzo Ferrari.

With these sensational exploits, the triumphal history of Alfa at Mille Miglia ends practically where, after the war, born that of a car whose manufacturer, trained and learned the trade in that same company, at Portello, which built its future glory, the Ferrari. Alfa left the races to private individuals who competed in tourism with its cars, all derived exclusively from the series, excluding, as we shall see, some sporadic official presence.

The 2500 reappeared, as mentioned, immediately after the war in the category reserved for them, the Gran Turismo, which was gradually growing in participation and interest. In 1947, Romano-Biondetti’s 8C 2900 B miraculously won, which was more an elegant but antiquated road coupe rather than a real racing car.

Romano-Biondetti’s 1939 model 8C 2900 B with its spectacular engine.

From 1948, year of Tazio Nuvolari’s exciting and moving race with Ferrari, the Alfa Romeo cycle was definitively closed and the Ferrari epic began, as we have said, with the overall victory of Clemente Biondetti. And it was a shame because if the 6C 2500 Sperimentali, instead of being entrusted to willing customers and well-known dealers (Bornigia, Venturi, Bianchetti, Rol, etc.), had been more followed and better guided, they would certainly have brought another absolute to the Alfa. It became clear at the Mille Miglia in 1950 when Fangio and test driver Zanardi took over driving the Sperimentale who, had they not been slowed down by various mechanical failures, due to poor preparation of the car, would have won without problems instead of finishing third overall. Bonetto’s car was fantastic (sixth overall in 1951), a rather hybrid Alfa derived from the pre-war 12-cylinder V-shaped Grand Prix of 4500 (Tipo 12C 1936), deprived of the compressor and bodied by Vignale. The presence of Alfa at 1953 edition was more incisive, the last attempt in chronological order to bring an Alfa to the top of the race, a success that would have been very useful as a return to the image of the manufacturer, which was to promote the sale of the new 1900 and the next little Giulietta. Three new and beautiful berlinettas were lined up (the Tipo 6C 3000 CM) with 3500 cc engines and over 240 hp of power, an evolution of the 3000 Sperimentale designed by Giuseppe Busso, and bodyworked by Colli.

Brescia, 1951. The Bonetto’s 412 Vignale.

Brescia, 1953. The 3000 CM by Manuel Fangio and Giulio Sala (known as Saletta, due to its small stature).

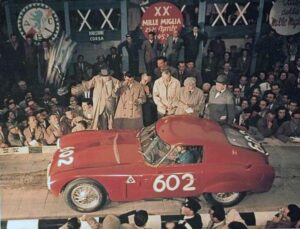

The 3000 CM was the result of a rather hasty project and set-up, carried out even a little in secret because the General Management did not like at all that important resources such as good designers and mechanical experts were subtracted from mass production and distracted by the dreams, very expensive, of the races. In spite of this state of affairs and although history tells us today the opposite with the success of Marzotto’s Ferrari, the three 3000 CM, and particularly the number 602 of Fangio, were the real dominators of the race with absolutely sensational averages. For the four-fifths of the course the three Alfa were always in command; then a little bad luck but above all the lack of real testing and therefore their poor tuning caused even trivial failures that mortified an amazing result and now within reach. Only Fangio and Sala reached the finish line second overall with 10 minutes behind the winner Marzotto with Ferrari. And to think that all of Ferrari’s technicians came from Portello. The company put an end to official participation in any type of competition to dedicate every resource to mass production and the market. Since then, for about ten years, only private drivers and many fans of the brand were the ones who unofficially brought to the race, on the road and on track, those same cars that were bought from the nearest dealer; it is no coincidence that a famous slogan from Portello at the time declaimed that the Alfa was “the family car that wins races“! And a better definition could not have been given to the new Giulietta, a true reaper of successes. And just to close the story, as well as the story of the Mille Miglia, in 1957, the last year of the race that inflamed Italy, the Giulietta Sprint Veloce of the Frenchman Martin ran an average of 126 kilometers per hour for 1600 kilometers.12 hours and 39 minutes; only six and a half hours less than it took Campari to win the 1928 edition!

In short, was the legend of Alfa Romeo son of the Mille Miglia or was it not the Mille Miglia that made Alfa Romeo legendary? In any case, both have written many beautiful and exciting pages of the entire automotive history, not only in Italy.

Stefano d’Amico

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes and belong to their respective owners.