Consalvo Sanesi, the man who said no to Ferrari.

Consalvo Sanesi, born in 1911 in Terranuova Bracciolini, near Florence, and died in Milan in 1998 where he had moved as a child with his family. Like many men at Alfa, he lived in Corso Sempione, a few hundred metres from Portello, where he was taken on as a mechanic by Jano, thanks to a “recommendation” from Gastone Brilli Peri, also from Tuscany, from the village of Montevarchi, close to his own.

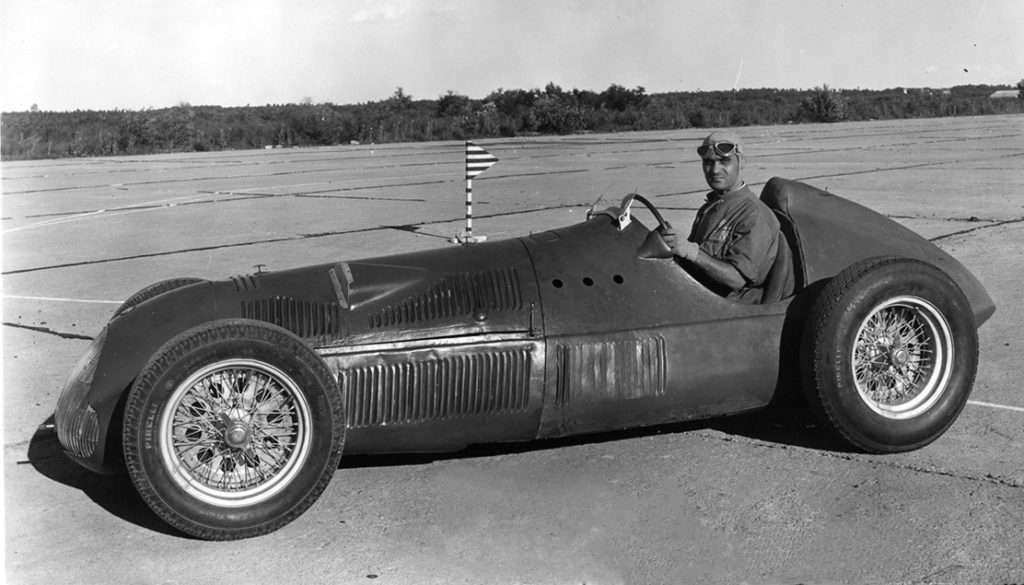

He worked close to the famous drivers of his time, most of all Campari who refined his talent, already inherent as a tester. He didn’t want to following Alfa Romeo’s sports activities in Modena, which the Scuderia Ferrari were in charge of at the time, and stayed at Alfa as a tester, first under the great Attilio Marinoni and then with Giambattista Guidotti, but the two never had a great relationship; Guidotti “envied” his ability, not so much as a tester but as a driver, that Consalvo could finally make come true with the birth of Alfa Corse, created by the Director General Gobbato who was dissatisfied by Scuderia Ferrari, and who placed him in the single-seater 158, designed in Modena by Colombo and Massimino.

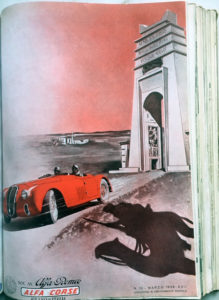

Together with Ercole Boratto, Mussolini’s chauffeur, he won the Tobruk-Tripoli in 1939 with the 6C2500 SS, a trek of 1200 km on the wonderful African highway recently built by Italians which then carried on to Bengasi (Via Balbia, more than 1800km).

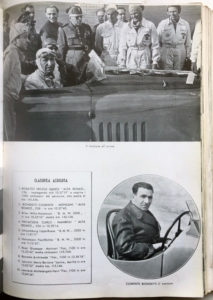

The cover of the Alfa Corse magazine, March 1939.

Sanesi and Boratto, winners with an average of 141.416 km/h.

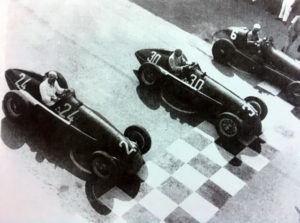

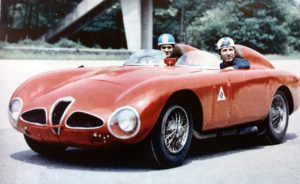

During the war, all the Alfa Romeo experiences division (ESPE) was transferred to Orta, in Piedmont, near Novara, to escape from the German raids and the allied bombings that destroyed Portello in 1943, while the racing cars were “walled” into a well-hidden garage in Melzo and retrieved at the end of the war by Sanesi himself, who towed them literally to Portello with a truck, through a half-destroyed Milan. In 1946, Sanesi finally became an official racing driver in the Alfa Romeo team together with Farina, Varzi and Trossi, while also remaining head tester. The 158 were updated, made more powerful and improved, allowing Alfa to win two World Championships in 1950 with Farina and in 1951 with Fangio, with Sanesi himself winning important positions. He took part in Mille Miglia with Zanardi and Fangio, but never managing to reach the much deserved success due to stupid mechanical problems and lots of bad luck.

The challenge between the Giulietta Spider and the extremely fast (at the time) Milan-Rome Settebello train was legendary. Sanesi won easily, reaching Rome three quarters of an hour ahead of the train, in spite of several ups and downs along the journey (punctures, refuelling, the bends on the Via Cassia, as the Autosole motorway finished at Florence…). His impulsive skill, he even did handbrake turns with the Duetto spider on the bridge of the transatlantic Raffaello, and the undoubted ability that didn’t however stop him from having some spectacular accidents like the one in Sebring in 1964 with the Giulia TZ, where he risked dying burnt alive if he had not been saved by a brave Alpine mechanic, Joco Maggiacomo, who he stayed in touch with.

Aside from the races, Sanesi was the person who decided on all the Alfa Romeo cars made after the war, the ones that decreed the real rebirth of Alfa, and his decisions were almost “law” for productions and for the designers, who trusted him totally.

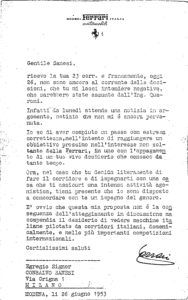

Such a technically, complete and expert tester, driver and mechanic could only attract the admiration of Enzo Ferrari too, who, right from the 1950s when Alfa left the races and knowing Sanesi’s passion, continuously praised him and tried to take him on at Ferrari as an official racing driver. There were months of doubts, arguments, words, sleepless nights, endless letters, interviews and praise in the Sanesi house… His love and loyalty to Alfa Romeo won the day, however, more than the suggestions from his family, who were tired of his battles on the tracks and hospitals all over the world. Although unwillingly, he refused the offer and Ferrari’s willingness to even triple his salary (a sensational offer for Ferrari to make!) and offer him free use of an apartment in Modena. Ferrari’s letters, shown here, confirm his determined interest to hire Sanesi and Consalvo’s emotional hesitation, as he was a simple, shy person, small but full of heart.

In the mid-1990s, he already couldn’t’t walk well, and I went to visit him with Maurizio Tabucchi. We recorded a great interview that we donated to Lorenzo Ardizio, the Director of the Alfa Romeo Museum and Document Centre. We then invited him to the Riar assembly that I was chairman of, to remember the gestures, reward him and allow the members to meet him. He was accompanied by her daughter to Arese, in a car not belonging to the group and the Alfa (Fiat) directors, even though they knew who he was, wouldn’t let him in (!!), in spite of the heavy rain and a clear difficulty in walking… He wasn’t offended; he walked the whole way, humbly and without complaining, but we were all disappointed. For the sake of being there. These were the Alfa men. The real ones. The real Alfa.

Stefano d’Amico

On the cover: Consalvo Sanesi on Alfetta 158, 1946

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes and belong to their respective owners..