Remembering Antonio Ascari

The resounding result at the French Grand Prix held in Lyon on 3 August 1924 and won by Giuseppe Campari was only the beginning of the great Alfa Romeo legend. A new triumph awaited the P2s on October 19, in Monza, at the Italian Grand Prix which, although postponed for a month due to a lack of participants, did not see the participation of the powerful Delage and Sumbeam cars which, sure of their defeat, did not turn up. The four Alfa Romeo cars, powered by the new super fuel “elcosina” made at Portello in collaboration with Shell and entered with drivers Antonio Ascari, Louis Wagner, Giuseppe Campari and Ferdinando Minoia, ranked, in order, obviously the first four places.

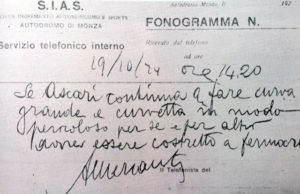

This race went down in history also because the legendary race director, Arturo Mercanti, officially ordered the Alfa Romeo team to slow down the speed of Ascari, in the lead with a wide margin and sure winner, claiming that according to him, Ascari was risking too much and uselessly! During the 44th lap out of 80, Zborowski in the Mercedes went off-road at Lesmo, skidding on an oil spot, and died due to serious injuries. Mercedes, as a sign of mourning, withdrew the cars (drivers: Werner, Masetti and Neubauer, the future legendary sports director of the Stuttgart company).

In Lyon, Enzo Ferrari retired from racing with the excuse that he was not well and was strongly depressed but in truth, as he honestly confessed later, he understood that he felt inadequate for the growing power of the big Alfa Romeo and preferred to do something else.

The 1925 season, during which the F1 World Championships started, saw therefore Alfa Romeo particularly favored; in fact, Ascari immediately won the Belgian Grand Prix held on June 28 on the new track of Spa in front of Campari and without any mechanics sitting beside him according to the new regulations for Grand Prix races (not only for obvious safety but also because, said and declared openly, nobody wanted to seat there anymore!). It was the last win of the great Antonio.

Alfa Romeo further upgraded its P2s for the occasion by assembling two carburettors and improving the brakes; Delage instead equipped with Roots compressors each bank of its 12-cylinder V engine, but it was not enough. In fact, the famous event of the snack, which became legendary, took place at Spa. Jano, annoyed by the excessive nationalism and by the whistles of the French public already accustomed to the continuous and overbearing wins of Benoist and his unbeatable Delage and therefore hostile to the impeccable Italian team of Alfa Romeo for its efficiency and for the clear overwhelming power of its cars, with a sudden and bizarre decision, made the drivers stop at the pits, who however had a considerable lead on other competitors. As soon as the astonished drivers got out of their cars, they were invited to an improvised snack around a table set in a hurry with cold cuts and wine, just in front of the pits so that everyone could see; while the cars were being supplied, cleaned with forced slowness checked and verified by the mechanics in every detail, so that they could show up at the finish line not only the winners but also in the same conditions in which they started!

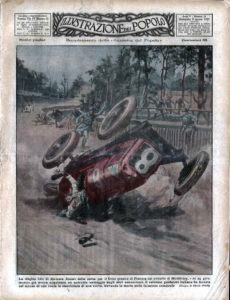

On July 26, the French Grand Prix, also held on a new circuit in Montléry with 80 laps for 1000 km, was affected by the death of Antonio Ascari; he was only 36 years old. The strong driver, who immediately went to the lead, during the twenty-third lap, some say due to an issue to the car that already started to sway for some laps and some instead say due to the asphalt made slippery by the rain that had begun, lost control of the P2 to the fast curve of the Hostellerie Saint Eutrope that for 22 laps always faced at about 180 km/h (!), hit the fence, went off the road, overturned and died while he was being transported to the hospital. Alfa decided to immediately retire the team as a sign of mourning, although, after the accident, Campari was clearly in the lead. Jano recalled in an interview with journalist Griffith Borgeson that Nicola Romeo, retiring the team at a time when both Campari and Brilli Peri were stopped at the pits, told him: “Jano, here we don’t race with a dead in our team”. Jano, troubled and moved, gave order to the mechanics in the pits, lined up next to their cars, to pack the engines of the two P2 in agony as a last salute to the great driver (Luigi Fusi, still in the 80s, remembered with tears in his eyes the tachometers went well beyond the 7000 turns allowed!) to then be silenced all day with the great sadness and emotion of those present and the spectators that had gone completely silenced.

A piercing roar that many journalists present, and even Mr. Ferrari, would remember for years.

At the end Benoist and Wagner, who won the race, brought themselves with their Delage to the accident location and set on the ground their laurel wreaths and flowers given to them for a victory certainly not earned.

Antonio Ascari, born September 15, 1888 in a small village Bonferraro di Sorgà, in the province of Verona, near Castel d’Ario (only 4 kilometers) in the province of Mantova, where then Nuvolari was born four years later.

“The two families knew each other and their roots were very close” (Enzo Ferrari). “Not very tall, athletic, blond, elegant, very good with business, they called him the ‘Maestro’, I must give credit that my work not even as a pilot, but as businessman in that passionate environment was greatly influenced by his example. He was a strong and generous character … he would always pay for everyone” (Enzo Ferrari). After having worked in Milan as a mechanic, he moved on to the Officine De Vecchi, to be the head of the repair department, where the car of the same name was built with which he began to race in 1911 at the Sei Giorni di Modena. It was there that he met Ugo Sivocci that also raced with a De Vecchi (Florio Plaque of 1913). The De Vecchi (1905-1919), an interesting car that was sold even in Russia, was absorbed in 1920 by the C.M.N. and Ascari, noticed by “those” of Alfa Romeo, in particular by Sivocci, went to Portello.

He was Alfa Romeo’s general representative for Lombardy with a dealership in Milan in Via Traiano. “Under his innovative drive, he built the ES Sport, which gave the Milan-based company its first success and commercial notoriety” (Enzo Ferrari). “Bold and improvising, a true “garibaldino”, as we say in the jargon of car race drivers who put courage and emotional charge before carefulness in studying the race track, who can guess the curves every time, trying lap by lap to get as close as possible to the extreme limits of roadway grip.” (Enzo Ferrari). He too was an idol for all sports enthusiasts.

Giulio Ramponi, the famous mechanic of Alfa Romeo, recalled that the night before the French Grand Prix, Ascari was very nervous and asked him continuously if he had checked this or that on his P2, which was something he had never asked. “That man had something that impressed” (Giulio Ramponi), as Cesare de Agostini also noted in an interesting booklet dated 1968.

However, there is also another version, unfortunately confirmed by various witnesses of the time, on the reasons that led to the death of Antonio Ascari at the GP of France. This version was told by his widow, Elisa, in a famous interview in 1952 to journalist Lamberto Artioli of the Gazzetta dello Sport. “At Montlhery some spectators, realizing that Ascari would win again, annoyed by the excessive Italian power and by the affront of the previous year, threw on the track in an isolated point some barbed wire that served to delimit the track but that, getting entangled to the wheel hub, prevented the driver from turning and caused skidding, flipping and his death. His son Alberto also confirmed this version of the story regarding the barbed wire, attributing, however, perhaps diplomatically, his presence on the track to carelessness or fate and not to the fans of the local champions. A merciless fate, however, that also struck Alberto, F1 World Champion with Ferrari in 1952 and 1953, in Monza on May 26, 1955, while he was driving just for fun, before lunch, wearing suit and tie, a Ferrari 750 Sport. He was born in May and just like his father, he was only 36 years old.

Stefano d’Amico

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes and belong to their respective owners.