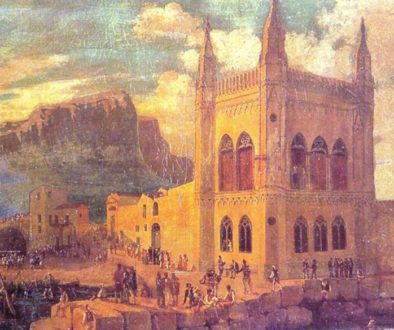

The XXI Targa Florio (May 4, 1930)

The Bugatti car, winner of the five previous editions of the race, joined in with its powerful and lightweight 8-cylinder 2300 supercharged engine, participating with a number of drivers including three truly experienced ones: Divo, already winner of two Targa race editions; Conelli, winner of second and third place in 1927 and 1928 respectively; and Chiron, who recorded the fastest lap in 1928. Alfa Romeo reached Termini Imerese with a remarkable team as well, constituted not only by the 6C 1750 Gran Sport compressore cars, winners of the last two Mille Miglia, but also by two old 8-cylinder P2 cars, widely updated and modified, especially in the chassis, very similar to that of the 1750 ones. Aesthetically, the radiator was flat but very sloped and its rear end (which also served as a fuel tank) pointed, like a Bugatti’s, but with a wide slot in the center where to house the spare wheel. The drivers selected by Jano were Nuvolari, Varzi, Campari, Maggi, and Ghersi. Among them there were the Maseratis of Borzacchini, Arcangeli, and Ernesto Maserati himself and the OMs of Minoia, Morandi, Ruggeri and Balestrero.

Cleverly, Florio made available to some important journalists (Faroux, Meurisse, Canestrini, and Bradley) his personal car, a large Fiat Torpedo marked number “00”, driven by his trusted driver Mario with the permission to drive freely along the track and to provide a live report of the race.

However, shortly before the start of the race there was a bit of turmoil at the Alfa Romeo pits. Campari, even if used to showing off and daring feats, strangely did not feel comfortable driving the old P2 modified in a hurry and thus not well tested, powerful (175 HP) but not very handy, on a winding and treacherous track as that of the Targa race. Moreover, unlike the more comfortable 6C 1750 Gran Sport, the small cockpit of the Grand Prix P2 was literally a furnace due to the heat coming from the engine, obviously positioned at the front, and from the rear oil tank, not at all mitigated by the typical slits of the coupe-vent, and therefore, with the addition of the heat of a spring day, driving the car in a race that was already exhausting seemed an extremely tiring task for Campari, the “Herculean gladiator”. Jano understood the problem and offered the Milanese driver Ghersi’s fourth 1750 Gran Sport, the spare car.

And so it was Varzi, a rising driver, young and ambitious, who had to drive the obsolete Grand Prix car that, besides, he had driven until a few months before. Jano, certain that Varzi would not be able to finish the race, took precautions by keeping Pietro Ghersi close to the pits to replace him in case Varzi failed to drive for all the five laps, which were 70 miles each.

However, right from the start it was surprising to see how easy it was for Varzi, just 26 years old and strong, to “control” the big and powerful P2 marked with number 30, the same number of the year of the race, so much so that, after only thirty kilometers, with each car beginning the race three minutes from the other, he had already built up an advantage of one minute over the strong Bugatti of Louis Chiron before him. At the end of the first lap, with Varzi definitely in the lead, Nuvolari second and Campari third, there were three Alfa Romeos ahead of as many Bugattis. On the second lap, for the delight of the audience, Varzi was still in the lead followed by Chiron almost four minutes behind him, while Nuvolari and Campari were respectively third and fourth. On the third lap, Varzi was still in the lead, followed by Chiron at less than two minutes, and Campari and Nuvolari right after them but switched in their positions. The fourth and penultimate lap raised the stakes because the Bugatti of Chiron, gaining ground, had almost reached the P2 of Varzi, just a few seconds away while Nuvolari was third again and Campari had slid into fifth position. But Varzi continued to be still in the lead on the fifth lap, marching on undaunted with a two-minute advantage regained over Chiron. Campari was fourth with the third gear unusable and Nuvolari fifth with the fore-carriage damaged (the eye of the front leaf spring was broken).

The fifth lap finally came. The last one! But the fight for victory was always very uncertain and the real pain had yet to come. The P2, because of ups and downs caused by the road surface damaged by the recent rains, received damage to the belt fixing the rear central spare wheel, which fell on the racetrack and caused damage also to the anchoring pin, which, in turn, caused the puncture of the gas tank that started to leak fuel. The spare wheel was then picked up by the English journalist Bradley, direct witness of the event together with the other journalists on board Florio’s car and the P2, almost running out of fuel, began to “sputter” and slow down.

It was total panic. Many fans rushed to the road to cheer and try to push the “limping” car but they were immediately pushed away by the screams and insults of the two Alfa Romeo drivers nervous and terrified of being disqualified because they were helped. Near Campofelice, an ancient city of Arab origin, with the P2 almost at a walking pace, Giannella, Varzi’s mechanic, without getting out of the car, grasped on the fly a can of fuel handed out by a service mechanic and poured gas into the tank with the car running and gradually accelerating. Fortunately for Varzi, Chiron, was behind him and delayed by a slow change of tires carried out by his Alsatian mechanic, exhausted and in bad conditions, terrified and full of bruises in the ribs due to Chiron’s punches who was upset by his fear. It was the first time he participated in a race and what a race!

On board the Alfa Romeo a good portion of the fuel – due to the jolts and increasing speed – ended up being spilled also on the huge and red-hot exhaust pipe, immediately catching fire and causing serious burns to the hands and arms of stoic Giannella who tried to extinguish the flames with his own seat while Varzi, without stopping, continued to drive like a maniac all bent forward to leave room for his co-driver who was already stretching half out of the already narrow cockpit, risking every moment to fall and kill himself. They both showed considerable bravery and cold blood: if they had stopped, the flames would have caused a large fire that would have engulfed them too, already soaked in fuel. Instead, carrying on at full speed, the wind brought the flames away farther and farther from their shoulders.

Luckily the fire was extinguished – mainly by willpower and sacrifice – but almost another precious minute had been lost. “Varzi, very excited, roared through Campofelice, still with the fire behind his back and rushed into the last long stretch like a missile, along the coast, with the engine running at 6500 rpms: this was not the time to be prudent. The red cars won and Italy was enthusiastically happy” (W.F. Bradley on The Autocar, June 1930).

The high-pitched, repeated, and prolonged acclamations of the enthusiastic Sicilians charmed by the show, all crowed at the edge of the road and on the surrounding hills around Cerda could be heard from miles away echoing in the air and they even reached the Alfa Romeo pits where everyone understood what had happened and breathed a big sigh of relief, recognizing the distant and familiar roar fast approaching. And so did everyone else rushing to the pits of Alfa Romeo, excited and moved, to applaud the courage of Achille Varzi and the regained supremacy of an Italian car.

Varzi won with about two minutes advantage, even winning 1000 British Pounds as well as various trophies and medals, and Louis Chiron won a well-deserved second place. Carlo Alberto Conelli won third place on the other Bugatti, while Giuseppe Campari ranked fourth and Tazio Nuvolari fifth. At the finish line everyone cheered Alfa Romeo.

“Gianferrari and Jano, surrounded by Sicilian aristocracy and journalists, are complimented and honored also by His Excellency Italo Balbo who had unexpected showed up in Palermo to witness the national triumph that marked the return to victory of his countrymen and their cars.” (Rapiditas, 9th Vol. – 1929/1930).

“The crowd is going wild. Alfa Romeo breaks the cycle of Bugatti’s victories, beating every record hands down. A truly Italian victory for man, racing car and tires” (Corrado Filippini wrote on Il Littoriale).

There was never a racing car capable to leave the races and the scene with greater glory, contributing to strengthen those strong feelings of national pride that also gave life to a multitude of fans and great enthusiasm for Alfa Romeo and its indomitable and reckless drivers. They were the symbols of a “new, hard-working, fascist and victorious” Italy, thus creating new unbridled and strong passions, like those powerful twin-shaft engines, which were then the real basis from which the myth of the “red” cars was born.

The P2 (chassis No. 40015 – Engine No. 3632) with which Varzi won the legendary Targa Florio of 1930 is the one modified by Jano and preserved today at the Carlo Biscaretti Museum in Turin (donated 40 years ago by Alfa Romeo), perhaps less beautiful than the one in its original form at the Arese Museum (apparently, former Ascari) but certainly more glorious. Biscaretti’s P2 has a beautiful history. First of all, it was the one that allowed Campari to win in Lyon in 1924 and that he used privately later, achieving many more victories, after having bought it from Alfa Romeo in 1925 and leaving it always as it was, even if with a few minor updates, until 1928, when he retired because he wanted to become an opera singer (but that period lasted a short time!). He sold it for 75,000 Italian Liras to Varzi, who wished to own a more powerful car than his Bugatti that he used to being his car racing career leaving the motorcycles racing world, helped by a loan from his Sunbeam motorcycle agent for whom he raced. Said car raced again in Monza, with Varzi as a driver and also with Campari himself – who, of course, gave up on his commitment to become a singer quite quickly – and also raced throughout 1929 winning several times, until Varzi resold it at the end of the year to the company where Jano made the aforementioned modifications, still visible today, for the 1930 Targa Florio race.

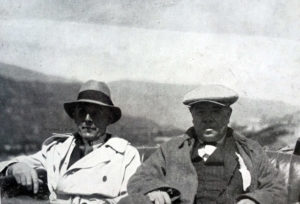

Nuvolari e Varzi

Tazio Nuvolari, “the flying Mantuan”, was born in Casteldario (Mantua) on November 16, 1892 and died at his home due to illness in Mantua on August 11, 1953. Small and thin, but with exceptional physical resistance. A lot of nerves. A great shooter, motorcyclist champion, cyclist, chain smoker, strong and daring driver, protagonist of sensational exploits and exciting races that turned him into one of the most exciting and solid myths in the history of the automobile and sport in general. Usually he wore a canary yellow shirt: “I am sure that that shirt will bring me luck. If I could not wear it, I would race unhappy” (sic T.N.). “He drove a Chiribiri, he came from motorcycle racing. That small, caustic man impressed me so much that I kept an eye on him and approached him on every possible occasion” (sic Enzo Ferrari). He tested the P2 at Monza, nearing the Ascari record and convinced everyone of his skills, but, due to an excess of enthusiasm, he went into a slide and overturned, suffering serious injuries. He was almost thought dead, but instead after three days, all bound and plastered by his trusted doctor, also from Mantua, according to his specific instructions that took into account the position to have on the racing motorcycle, was laid down by the mechanics on the Bianchi 500 and won, with considerable physical pain, an incredible and exciting Nation Grand Prix. The press and the fans went wild and so his legend was born, the one that filled, since then, pages and pages of newspapers, entire books and numerous monographs in the course of his countless “activities”. A true encyclopedia to which the passionate reader must refer.

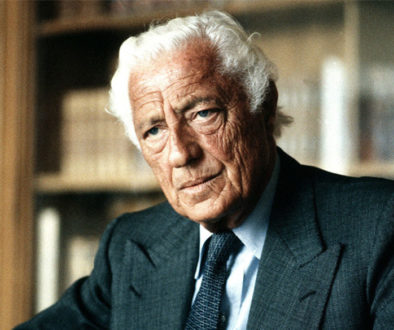

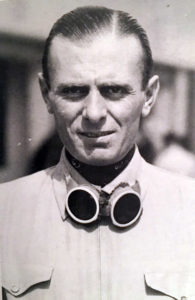

The Achilles was born in Galliate (Novara) on August 8, 1904 and died in Bern, at the Swiss Grand Prix, on July 1, 1948, while he was testing the Alfetta 158 on the same racetrack where, a few hours earlier, even Omobono Tenni with the Guzzi had died. “He was driving for the first time on a wet racing track the 158 equipped with a two-stage compressor. A car that had about thirty more horsepower and that unloaded that power in an almost brutal way. Jean Pierre Wimille just overtook him…” (See Giorgio Terruzzi – Una curva cieca [a blind curve]). In 1926, after several motorcycle racing victories, he drove, like Nuvolari, a small Bugatti 1500, painted green, on the Monza racing track, where, in memory of Antonio Ascari, the “Club dei 100 all’ora”, promoted a few races. To join this exclusive Club the aspiring drivers had to overcome in a given period of time an average speed of one hundred kilometers/hour on the ten kilometer long racetrack. And it was not easy! So much so that the press, even if curious, deplored this type of absurd and anomalous procedure of “admission” due to the continuous accidents it generated. Varzi was nicknamed by his friends and fans “el legora”, the hare. “Achilles calm, steady, and accurate took the lead of the race after skillfully taking advantage of the inevitable misfortunes of his competitors; the fiery Tazio, always chased the competitors in the desperate and often successful attempt to gain ground” (Cf. Cesare De Agostini). A smoker, smartly dressed and elegant, a player and a hunter. In 1935 he fell madly in love with Ilse, a beautiful young German woman, wife of Auto Union driver Paul Pietsch, who unfortunately used morphine and offered him some. It was the beginning of the end (see Giorgio Terruzzi – Una Curva Cieca). “A calculating person, pedantic, a stylish and tidy driver, as in life. Unlike Nuvolari – who considered the car a means of fighting and conquest, glory and popularity – Varzi deemed the car a tool to satisfy an inner need, to affirm his own personality, to satisfy himself” (Giovanni Canestrini). “In some races, that I watched and experienced, unfortunately only as a spectator, I saw in Varzi such a range of stylistic and tactical subtleties that really impressed me” (Felice Nazzaro).

We also report an interesting article written by Carlo Brighenti on the two Champions – Nuvolari and Varzi – so close in sport but so different in character and life, which appeared in a monthly supplement to the Secolo Illustrato of September-October 1933, during the peak of their career.

“Nuvolari or Varzi? The superiority between Nuvolari and Varzi must be considered from different points of view. First of all, there is the point of view of the fans, which is beautiful, because fans also live by passions, live by enthusiasm, live by idolatry. Then there is the less clean point of view of some of the journalists, who do not care about Nuvolari or Varzi, but bring up these topics to sell their newspapers … There are in fact sports events that are equivalent and you do not know which is the best … It is the beauty of a healthy sport … full of champions like the fascist sport of Italy. Juventus, which in the middle of the championship has the final victory in hand, unintentionally harms the sport because it flattens it, takes away the divine charm of uncertainty. The Guerra-Binda duel (two famous cycling champions of the time, Editor’s note), even if it is the cause of nasty disputes and boxing matches in front of bars, is very useful for cycling propaganda. The same is true… of the Varzi-Nuvolari duel. Varzi and Nuvolari are two champions of different temperament, one young and the other older, but they are two shining stars … Europe and America envy our champions and we do not have to bother them, we do not have to depict them as two dogs … ready to bite. If Nuvolari wins, the benefits also fall on the many workers who live in the Italian automotive industry. The fact that Varzi races for a French brand leads to benefits that fall on French workers. Personally, I am sure that they are, I repeat, two great champions, today the best in the world. Caracciola, Borzacchini, Chiron, and Fagioli are very similar to them and, when in the right mood, so is Campari. The other ones are lost in the fog.”.

Stefano d’Amico

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes and belong to their respective owners.

The video “A Palermo la XXI edizione della Targa Florio” is property of the Istituto Luce Cinecittà.