When Alfa Romeo cars were winning

… and to think that they were called P2

1925. L’ALFA – Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili – a young Milanese carmaker born from the bankrupt French Darracq, was gaining greater and greater recognition thanks to extraordinary victories in the world of racing.

They were heroic times, made of amazing discoveries and great exploits also due to the firm desire to “be reborn” after a devastating world war that lasted about four years.

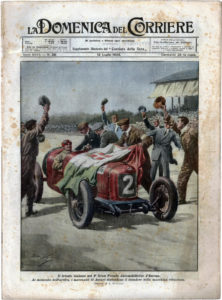

Albert Einstein formulated the Theory of Relativity, Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankamon, Lindbergh flew over the Atlantic, and in Rome the Boys of Via Panisperna (Fermi, Amaldi, Maiorana, Pontecorvo) made sensational breakthroughs in nuclear physics, while throughout Italy cars, the new vehicle of the time, stirred into action a multitude of imaginative and enterprising manufacturers, some of which became famous, and obviously they became more and more popular. In fact, the Milano – Laghi, the first motorway in the world, was inaugurated and in 1925 Alfa Romeo – after having dominated the Targa Florio race with its RLSS-TF driven by Sivocci-Guatta the previous year in Sicily – won the first motor racing World Championship with Ascari and Brilli Peri and from that moment until the seventies, its logo was surrounded by a laurel wreath.

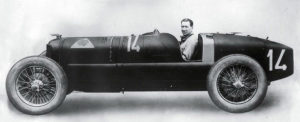

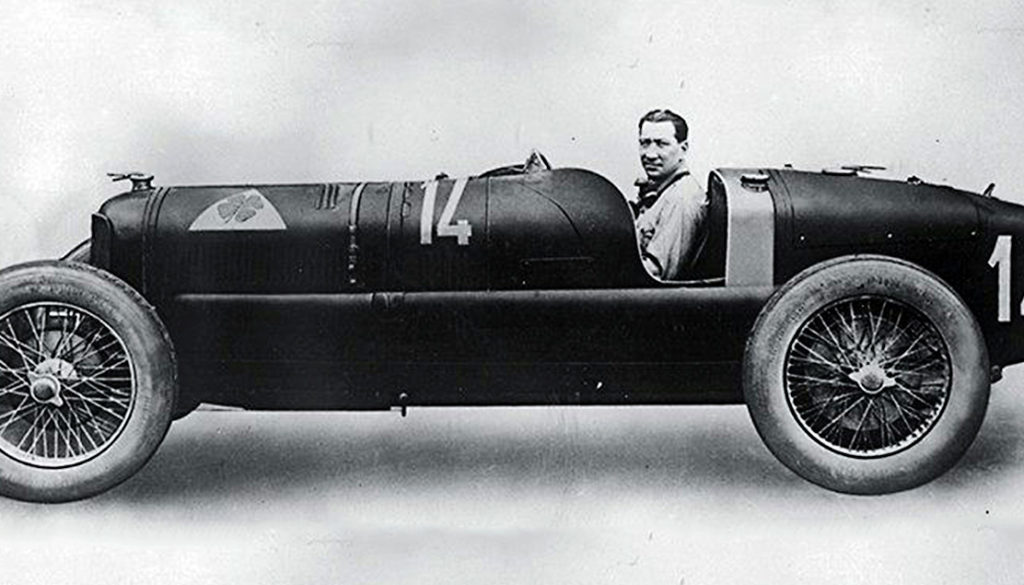

Certainly, this was not the merit of the regime of the time, which promoted its image also through the car and exalted the prestigious Italian victory, but to a handful of technicians who created an extraordinary car: the P2. P2, but not the one that inspired the Masonic lodge of Licio Gelli, but a perfect “battle-ready” vehicle that when in the capable hands of special drivers such as Campari and Ascari (and even for a short time of Enzo Ferrari) dominated for several years every car racing competition. Thanks to its brilliant competitive longevity, it even won a hard-fought and sensational Targa Florio in 1930, with Achille Varzi, making history and making Alfa Romeo a legend. But this is another charming story that we will tell later…

And just keep in mind that Tazio Nuvolari has not yet joined Alfa Romeo…

The first technicians were truly brave and ingenious pioneers, creative and very skilled, familiar with the most advanced technologies of the the time. Their undisputed leader was Vittorio Jano, who was “picked” in 1923 by Enzo Ferrari from Fiat based on a recommendation by Luigi Bazzi (also a former Fiat technician), and immediately hired by Alfa Romeo specifically under the request of Nicola Romeo. Ferrari, more than a good driver, had started to show off how good of an organizer he was as well as a man capable of choosing very skilled individuals. And Jano, who replaced Merosi, designed all the most significant and successful Alfa Romeo cars at Portello. The diagrams of his engines, light and powerful, like his cars, were the foundations of every success, both on the market and on the racing track, for the Milan-based company until our times!

The P2 was a truly exceptional car and its arrival was a real surprise in the world of racing; not yet fully ready, it immediately entered into action in 1924 at the Cremona racetrack where it broke the world record of ten kilometres at 152 km/h on average with peaks of 195 km/h beating the strong Chiribiri of Marconcini and the Bugatti of Malinverni. Canestrini wrote: “the silver vehicle proceeded steadily on a rather uneven track and the song of its engine reflected the immediate feeling of a greater power” (it was not red and it only featured 140HP!). It won easily in France at Lyon, with Antonio Ascari as its driver, and became the protagonist of its time. Unbeatable. Jano recalled in an interview with a journalist, Borgeson, that: “That day, the birth of Alfa Romeo at the level of the ‘grandes èpreuves’ was announced.” The debut in Lyon, which also marked Enzo Ferrari’s retirement from racing, was so sensational and ground breaking that caused the end of the career for many highly acclaimed cars. The Milan-based cars literally made everyone else eat dust, particularly at the French and Italian Grand Prix, where the Alfa Romeo race cars were ordered to slow down so as not to further humiliate their opponents!

The competitions of the time were dominated by Bugatti, Sunbeam, Miller and Delage cars. But, above all, by FIAT with its 801 and 805 GP cars, after Jano’s interventions on the engine and compressors. The humiliation for their burning defeat (specifically due to Jano, a former Fiat employee) was such that Senator Agnelli, severely disappointed, ordered the immediate withdrawal of the company from the races and the total destruction of its competitive Grand Prix cars. Legend says that they are still buried in Turin under the Lingotto. The supremacy of the Milan-based racing cars with their green four-leaf clover over a white field, painted on the hoods and destined to become the symbol of the Alfa Romeo racing cars, completely upset the balance among the various carmakers and forced the FIA, in 1926, to change technical regulations and type of formula and therefore Alfa Romeo was forced to withdraw from this type of competition.

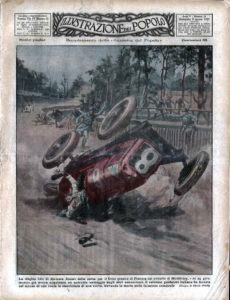

The French Grand Prix at Montlery in 1925 was overshadowed by the death of the great Ascari and as a sign of mourning Nicola Romeo withdrew the team while the mechanics at the pits pushed those powerful engines well past the 6500 rpms for which they were designed, as a last farewell to the great champion. A powerful and wailing roar that many witnesses and journalists of the time will remember for years. Luigi Fusi, Jano’s aide and future organiser of the Alfa Romeo Museum, was among them, and even in the early eighties he was still telling this story with great emotion and wet eyes.

And so the Tuscan Count, Gastone Brilli Peri, followed by the other P2s driven by Campari and De Paolo, easily won for Alfa Romeo and Italy the First World Championship in Monza, in September of the same year. As usual. In 1926, Alfa Romeo sold the six P2s not only to a young rising star, Varzi, but also to a few private drivers (Campari, Brilli Peri, Kessler) and to Genoa-based Alfredo Nasturzio, who turned it into a two-seater car for road use (!) by adding mudguards, headlights and electrical system. In 1930, Alfa Romeo itself bought back three of the cars to enroll them in a few racing competitions.

Here is the opinion of Cino Moscatelli, turner at the Trieste department in 1926, as well as a “professional revolutionary” and, later, partisan commander: “I always wore the Alfa Romeo badge (…). It was a symbol of prestige to work at Alfa Romeo. We recognised that Isotta Fraschini’s cars were beautiful luxury cars, for noble people. However, the racing ones, on the racetrack, could not compete with Alfa Romeo… they were unbeatable.”

And that glorious and ancient symbol, that already in 1950 and 1951, thanks to Farina and Fangio had returned honour and pride to Italy and to Alfa Romeo after WWII, has reappeared a few years ago on the Ferrari cars in the Formula 1 races, a romantic historical reminder wished for by Sergio Marchionne. Recently, it has also returned to the racetracks officially and directly, as the official sponsor of Sauber. And even with some success. Who knows… perhaps it will rekindle forgotten enthusiasm and stir up fan…

Stefano d’Amico

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes and belong to their respective owners.

Hi, I have read with great interest your excellent article regarding the Alfa Romeo P2.

My question: are you aware that the mentioned 4-leaf clover had only 3 leaves during the 1925 season (see attached picture)? Do you know why? In 1924 and after 1925, there were always 4 leaves, but not in 1925? Perhaps Sivocci’s death end of 1923? But why one year later only?